An Interview with Julia Schwartz

Julia Schwartz, Chutes and Ladders, 2020 Oil on linen. 24 x 18 inches

By Paul Maziar | August 25, 2020

Art Critics on Emergency is a real-time collective diary by AICA-USA members about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on art critics, artists, arts institutions, art education, and the arts at large. AICA-USA members are invited to submit journalistic reflections and critical observations about this moment as it unfolds.

“I believe an artist can speak from their heart to another about art.”

The concept of Nirvana is, in part, about transcending lived reality, wherein earthly suffering somehow disappears. But what’s the other side of that sublime presence, the complicated experience of everyday life? Art can be a way to bridge the apparent gap between attention to the world and its ills and renunciation or abandon. La Loma Projects is showing an online exhibition titled So Far, featuring two paintings by Julia Schwartz that stunned me. The gallery’s theme for this show is “portraits made by artists under quarantine, providing an interior view of the historic upheavals of 2020” and this, given the obvious imagination and play in Schwartz’s compositions, provoked the following exchange. I asked Schwartz about her process and ideas, to be reminded of the ways that in the midst of current uncertainties, art and life can merge. An exemplary facet of Schwartz’s practice is the commitment to approaching her work from a place of openness: keen to what’s happening in the world and with a deep sense of self. That her concern is so often in the social and political makes her visually stirring work a circuit to deeper meaning.

PAUL MAZIAR: Talking with you during the pandemic, in a time that feels like it’s verging on social collapse, I find it difficult (somewhat ridiculous) to talk about art and theory. There are so many other conversations to be had. But I suppose we’ll keep to your painting practice and your current exhibition at La Loma.

JULIA SCHWARTZ: I know what you mean—in the face of major life and world events, I find the way I work undergoes a radical shift. In the beginning of the lockdown, I spent most of my time making a book, a “covid diary” of collaged paintings that then became a record of the days leading to my father’s (non-covid related) death; and when the protests started, I felt like I couldn’t work at all, I just watched and read the news. It took a while before I could return to painting at all.

PM: I relate! I always feel that I’m starting anew (practicing a beginner’s mind), especially since the stay-at-home order, though now in an estranged kind of way. Language—a major way we situate ourselves in the world—undergoes certain changes when the daily practice of talking with others becomes, at best, mediated by screens. Now more than ever we search for new images that might help us make sense of our world, new language to relate our experience to one another, for understanding and surprise. I’m reminded that art is the best way to embrace the full-force ambiguity we face.

Julia Schwartz, covid diary 2020, artist book, collaged newspaper and gouache, 11 x 8.5 inches (cover: don’t touch)

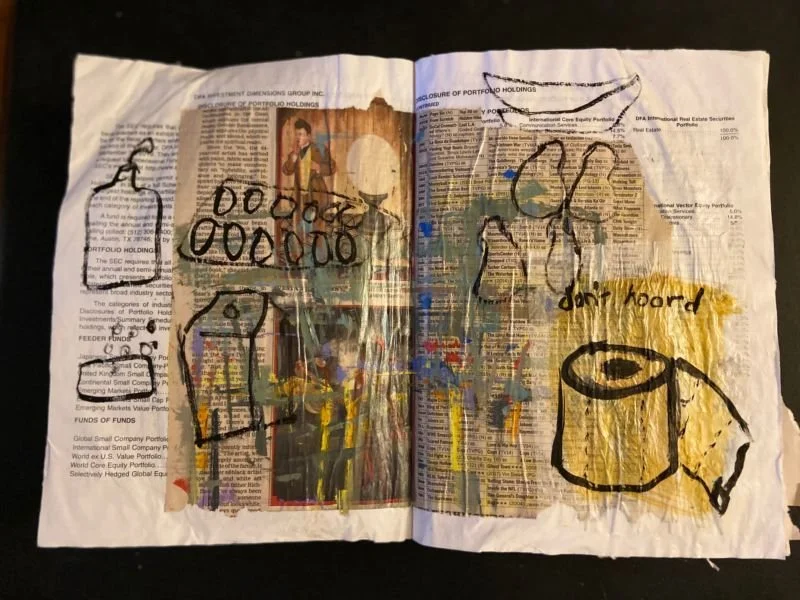

covid diary, 2020, artist book, collaged newspaper and gouache, 11 x 17 inches (don’t hoard)

JM: I like this very much, Paul, both your sense that we are estranged from everyday language (being at a distance from each other) and then needing to turn to other forms of communication, in a rather urgent way I’d add. I’d say that art is my way to address catastrophic events, to make sense of senselessness.

PM: To make sense of senselessness is it. And making an all new kind of sense. How did you arrive at the palette you’ve chosen?

JS: I used to joke that I was a "feral painter" because I never lay my paints out properly, never mix them properly. I use a large glass palette and dirty brushes in dirty oil, and leave the half-crusted paint on the palette from one day to the next so the color evolves over several paintings and several months, because that’s life, right? One messy day follows another. The colors I use on a regular basis have evolved over time, but these days they include: blues, umber, grays (graphite, Portland, torrit), pink, white, buff, yellow, and always green, many different greens, probably because my studio is a converted garage with a view of the garden. Right now there is yellow green, brilliant green, sap green, Courbet green. I make decisions intuitively—it has to look and feel right or it gets painted over. To be honest, the large expanse of white in Family Portrait (in So Far) was initially a way of dealing with a problem (bad painting) that led to something really exciting.

PM: Your work registers to me as playful and peaceful, and also somehow vulnerable—from your palette to your brushstrokes and mark-making. I find it remarkable how in-touch you strive to be, with our socio-political circumstances as well as your own emotional life. Do you find your composition practice to be one of processing what you’ve learned or experienced?

JS: I appreciate your reading of the paintings as playful and vulnerable; that’s a lovely balance. I would not say I try to achieve that: I hope I’m not repeating myself too much here from earlier interviews, but I’ve noted before that my “trying” usually leads to bad outcomes. What I mean is this: my preference is to stay out of my own way, get my head, mind, thinking, intention, ideas, and so on out of the way so nothing stands between color, brush, and surface. Early on, anything is possible; the painting emerges out of a kind of non-thinking back and forth: palette and canvas, non-thinking-me and painting. As things proceed, however, some decisions are made: editing, colors shifting, scrapes, shapes, mark-making. Some doors have to close in order for a painting to settle, although there is generally a lot of space for open interpretation even with a finished painting.

Julia Schwartz, Family Portrait, 2020 Oil on linen. 24 x 18 in

PM: That’s one suitable way to approach the painting from the standpoint of emotion. It might be necessary to enter territory that comes from places of vulnerability, shadows. The painting of you and your grandmother in the moment she collapsed is heart-racing. I’m reminded of Edvard Munch’s interior scenes. Once this painting was finished, did you feel that it affected your memory of the event in some way?

JS: I’ve never stopped to ask that particular question. I’m not sure it affected my memory exactly, but I can say that there was a point when I had repressed the memory, but now it has been seamlessly integrated into my life story. I imagine that story and its accompanying feeling-state still appears in my paintings but in symbolic and attenuated ways.

PM: To get back to Family Portrait from So Far, there’s the sense that things are appearing and disappearing right then and there, as you look at it. The composition also looks as if it could’ve begun with any of your given marks or strokes—the white giving way, as you say, to the exciting thing it became. The astonishing thing is, when making pictures, something develops seemingly out of nowhere, through discovery. This reminds me of Philip Guston's description [interviewed by Clark Coolidge in 1972] of a “third hand” at work. Does that idea interest you much?

JM: Yes definitely, I think that corresponds very much to those moments I was describing, when you can manage to stay out of your own way. I don’t know if I knew the phrase ‘third hand’ when I was trying to express my way of working, but I’ve referred to it as transitional space, “being-with” a painting rather than looking-at, and so on, attempting to capture a kind of non-thinking approach to painting.

PM: I understand you also work as a psychoanalyst. Do you think it’s possible for an artist to fully know the meaning of what they’ve made, and if not, do you see that as a benefit to the artist?

JS: I don’t know about fully knowing but I often come to understand the meaning(s) of a painting as I’m making it. Meaning is not the same as intention. I think there’s a difference between a conscious and deliberate intent like “I want to make a painting about X” and the more subterranean readings that can be discovered. Is it a benefit, knowing or not knowing? I think it’s an interesting question whether it’s preferable to make work without knowing what that deeper meaning might be; that might make a person feel self-conscious.

Sometimes, meaning doesn’t come until long after. For years I made paintings of female figures with spindly arms, practically invisible arms. It took several years before I made a connection to a traumatic childhood experience that had left me feeling simultaneously responsible and powerless. I’m pretty sure that once I had that revelation, those paintings were no longer needed, that series came to an end.

Julia Schwartz, trying and failing 2011, oil and wax on panel, 20 x 16 inches

PM: Right! This rings true to my practice of creative writing. Certain meanings may not arrive till later, and that’s often the ideal outcome—so as to not get in our own way during the making. Thanks, surrealists.

Looking at your pictures, thinking about So Far: “an interior view of the historic upheavals of 2020,” I started jotting down terms that seemed like they could be relevant to us both. In the spirit of playfulness, would you be into responding to any that resonate to you lately, as related to your work?

JS: You may know that I’ve been dealing with personally historic upheavals prior to 2020 which meant figuring out how to show what upheaval, disaster, and wreckage looks like in a way that is consistent with how I paint, not illustrative, narrative, but experiential and ambiguous, so this is familiar territory for me.

Solitude: I’ve always needed solitude going back to childhood. For years, my paintings were all about figures in solitude, that isn’t the case now but I think it still comes through. And then again, I’ve been living in a quasi-quarantine state for several years due to personal family circumstances. I think that comes through my work.

Intimacy: I feel like I’m in my best place when I’m in an intimate relationship with my materials, when there’s no other gaze to distract or please. Also, the word intimacy makes me think of the size of my paintings. I feel much more at home with small works, and tend to prefer them because of the intimate experience of viewing and making. Maybe it’s like Forrest Bess, whose work was all more or less the size of his head.

Air: Being in a semi-open studio is really important. Air, garden, birds, ambient noise.

Memory: Loss, and therefore memory, are big sources for my work because they are so much a part of my situation.

Night: I have made quite a number of paintings that have night in the title or dream or sleep or sleepless… perhaps you’ve picked up on something! I have two studio spaces, both at home, and the one in the house is my “night studio” where I work until about 1:00am. This is where I’ve made all my series on paper—books, handmade paper, prints, and so on. But night is also a sensibility, a time of vulnerability, when defenses are down.

Vulnerability: To be human is to be vulnerable. The way I know how to be an artist is to make human paintings, paintings that are vulnerable, without technical skill or prowess. And if a painting is dead because I’ve tried too hard, or used some trick, it loses its aliveness.

Home: Since painting is how I make sense of my (existential) situation/circumstance, home is a big part of that. Over the years, you will see other things come into my work—paintings dealing with the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, paintings made after the 2016 election, paintings in response to shootings, but home is ever present in my work, albeit in an obscured and abstracted way.