Every Day is a House Party: the Grief and Joy of Parenthood in Heather Owens’s Art

By Amy Kennedy | March 31, 2025

The Art Critic Fellowship is an art writing intensive program launched in 2025. Over eight weeks, fellows engaged in four lectures led by award-winning editors and writers to discuss the joys and concerns of writing and editing art criticism today, and met one-on-one with their assigned mentors to develop a piece of criticism for publication on AICA-USA’s Magazine.

Amy Kennedy is part of the 2025 cohort and was paired with Sarah Hotchkiss as her mentor.

Maybe it’s because my children are COVID babies, but when I spend a lot of uninterrupted time with them, I start to feel claustrophobic. I begin drowning in our too-small house or in my touched-out body with its stretched-out skin. On the worst of those drowning days, my partner will ask me if I’ve taken my medicine and then send me away, to a place that isn’t our 1,000-square-foot rental where colorful piles of toys and laundry and dishes are visible in every corner.

These childless field trips usually involve me trying to reconnect with some earlier version of myself, the person I was before children, before the pandemic turned parenting into an isolating endurance sport. On a recent trip, I found myself at the McGuffey Art Center in Charlottesville where local artist Heather Owens’s exhibit House Party stopped me in my tracks. The first piece I noticed was reminiscent of the generic “Live, Laugh, Love” cottagecore decor, the roughly stenciled words “This is My Happy Place” taking up the entire canvas. Peeking through in small, desperate red letters was “I wish I could leave.”

This Is My Happy Place, 2024. Colored pencil on canvas. All images taken by the author in Heather’s studio unless otherwise noted.

I shocked myself by laughing out loud in the quiet hallway gallery. And then I shocked myself further by tearing up. This small, simple piece was a balm. The guilt I felt for wanting to get away from the constant stimulation of motherhood disappeared.

Most of Heather’s work is like this; it makes me laugh and then teeter on the verge of tears, which also sums up my experience with motherhood these last eight years. In her piece Fun Style, a small canvas is covered in floral wallpaper and lace, a ceramic toilet in the center. The toilet and the lace are dingy and piss-covered, a reminder of my own constant battle with the single bathroom in our home that smells like urine no matter how often I clean it.

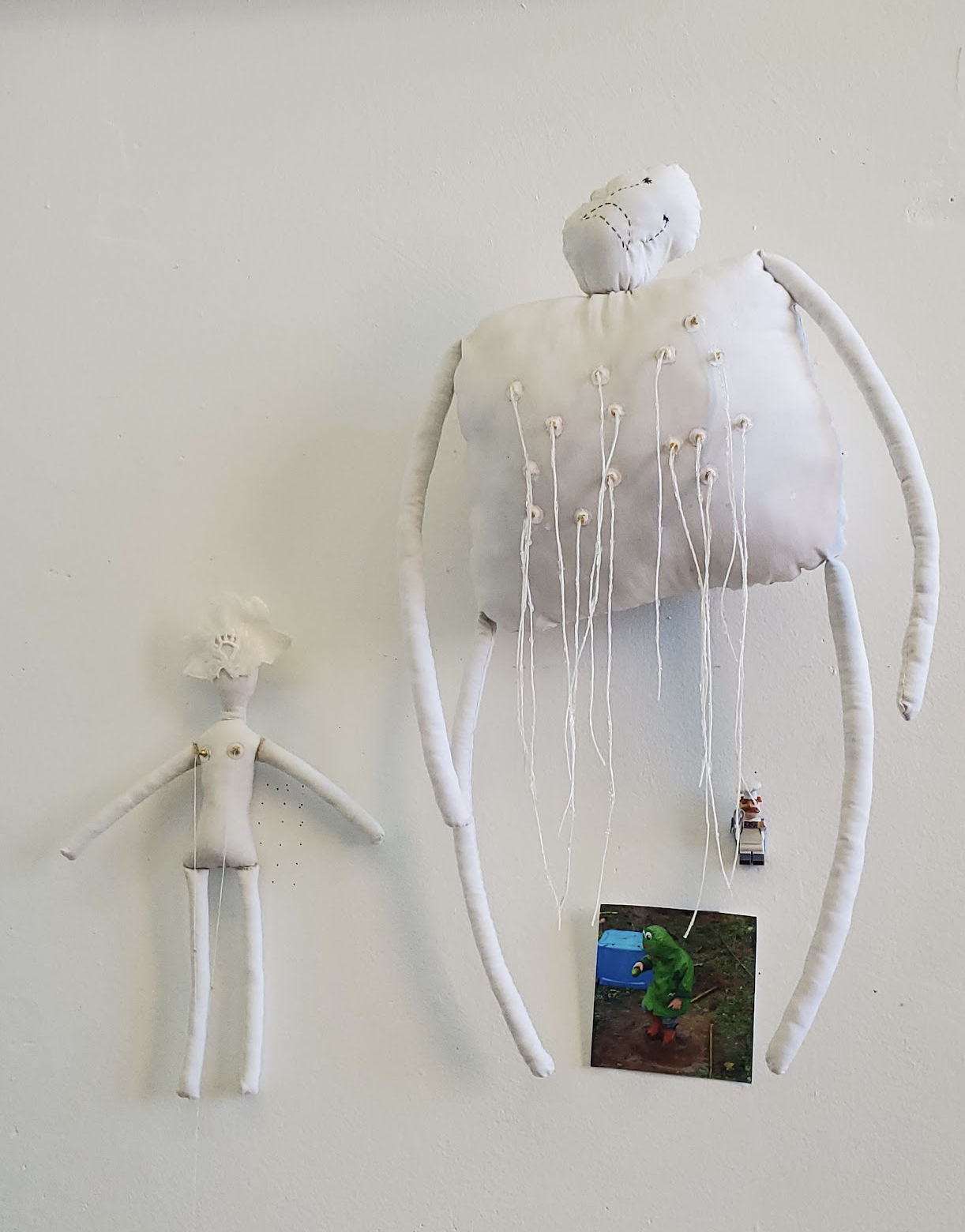

Another exploration of best intentions falling short against the demands of parenthood is Expectation and Reality. Two cloth dolls sit side by side, white strings hanging from them to represent breastfeeding. The Expectation doll is petite and demure with a lace bonnet and two dainty strings of milk coming from her small breasts. The Reality doll is monstrous and cartoonish, its entire bloated torso turned into a single breast with strings of milk bursting out uncontrollably. Reality’s distraught face reflects my own despair about breastfeeding, about losing my bodily autonomy again so soon after giving birth; it reflects the months of not sleeping more than a few hours at a time and the accompanying psychosis. The faint smell of spoiled milk from the nursing bras I wore through a Louisiana summer of breastfeeding is never far from my mind.

Fun Style, 2024. Mixed media assemblage.

Expectation and Reality, 2024. Found fabric, glue, earring backings. Underneath Reality is a picture of Heather’s son and a Lego Muppet figurine he stuck to the wall.

With the unmet expectations of motherhood comes concessions, and Heather’s Our Mother of Serenity captures the compromises parents make with their former selves to maintain sanity. In a found photo a woman appears to be full of divine light, both matronly and serene. Our Mother’s inner peace is untouched by the chaos erupting at the bottom of the frame, where Heather applied dozens of stickers in the haphazard way of children, with little attention to spatial awareness or orientation. It’s unclear if Our Mother surrendered tidiness for the sake of her serenity or if she’s dissociated altogether. But with the faraway look in her eyes, she’s obviously done something to keep the demands of motherhood from touching every part of her.

Our Mother of Serenity, 2024. Found photo collage. Stickers, acrylic paint, gold leaf. Photograph by Heather Owens, reprinted here with permission.

Complaining about parenting isn’t novel, but most of the loudest voices are doing it on social media, walking the thin, irreverent line between edgy and crass, and perpetually defending themselves in the comments. It is NSFW humor that speaks truths but feels unserious and separate from actual parenting. Heather’s work takes the sometimes-misery of parenting seriously from within the storybook setting of childhood. This contrast mirrors my own disorienting experiences with postpartum mental health struggles where the playful imagery of childhood is at complete odds with the darkness of my own thoughts. Heather’s work gave me permission to mourn the parts of myself that I lost when I had children, and she did it in a moment when my grief felt acute. (I was once a person who roamed around art galleries.)

After that gallery visit, I started following Heather on Instagram and realized I recognized her. Every day, I stood in line next to Heather after school while we waited for our kids, but I’d never spoken to her. I decided to introduce myself and tell her how much her work meant to me. We were both a little shy about it, as if we’d shared a personal moment without meaning to. Since I’d caught House Party on its last day, I asked Heather if I could visit her studio to spend more time with her work and talk to her about it.

A couple weeks later, I found myself back at the McGuffey, this time in Heather’s studio, looking at one of her biggest pieces, a portrait of her oldest son. It captures the overwhelming love parents feel for their children, the joy of childhood, and the complex grief parents harbor for their former selves. The boy is surrounded by a halo of butterflies. Throughout the painting, there are spots of light shining through the dark blue background, like pinhole cameras. The canvas was an unfinished painting Heather started before she had kids—a world that she couldn’t see anymore. Instead, she painted her son’s portrait over it. Her beautiful son, a prince who loves butterflies. The light surrounding him starts to dissipate the darkness on one side of the canvas, letting more of the background picture come through—the picture that was there before Heather became a mother.

Calvin with Butterflies, 2024. Acrylic paint. Photographed by Heather Owens. Reprinted here with permission.

And as I stood in Heather’s studio, I realized that I was once again a person who roamed around art galleries.

I still see Heather at school pick up, and I know most days we’ve both walked reluctantly away from our work. We’re both likely overwhelmed by the playground noises and the immediate needs of our children after school. Often, we take our kids to the park nearby to play for an hour or two before going home. She brings her sketchbook just like I bring my notebook, both of us hoping against reality that there will be a few moments of free time to do a little more of the work that keeps us sane. Some days, Heather and I will stand together with a few other parents, looking out as our kids play. I wonder if any of the other parents are watching and thinking about how hard it all is, trying to keep our kids healthy and alive in systems that don’t support health or life. I wonder how many of them also miss the person they were before they had children. And even though Heather and I don’t talk about it, just seeing her there and knowing that she’s allowed herself those same thoughts makes the whole thing more possible.

Heather Owens is a juried member at the McGuffey Art Center in Charlottesville, VA; her work is on display at her studio there. Heather’s work is also online at heatherownesart.com and @heather_owens_art (IG).

Amy Kennedy writes fiction and nonfiction about the ongoing climate crisis and the surreal spaces where heavy industry and community intersect. She created ALongNewThread.com, a website examining ecological grief and environmental injustice. Amy is a Loyola Institute of Environmental Communication Fellow, a DeGroot Foundation Courage to WRITE grantee, and a 2024 Anonymous Was A Woman Environmental Art Grant recipient. Her work has appeared in the Southeast Review and Burnaway. Her first book Vanishing Points: Words for Disappearing received an Antenna Press Publishing Award and will be released later this year.