Lines on Concrete: Najja Moon at Tunnel Projects

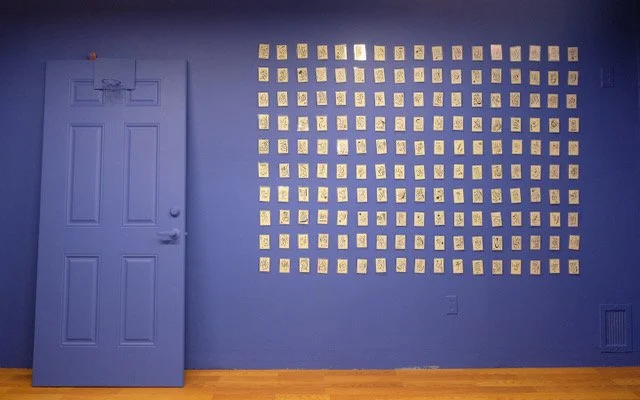

Installation view of Mate Masie by Najja Moon at Tunnel Projects. Image courtesy of the artist.

By Francess Archer Dunbar | March 31, 2025

The Art Critic Fellowship is an art writing intensive program launched in 2025. Over eight weeks, fellows engaged in four lectures led by award-winning editors and writers to discuss the joys and concerns of writing and editing art criticism today, and met one-on-one with their assigned mentors to develop a piece of criticism for publication on AICA-USA’s Magazine.

Francess Archer Dunbar is part of the 2025 cohort and was paired with Shiv Kotecha as her mentor.

In its most literal form, a tunnel refers to a passageway made underneath the ground or through an obstruction. In a city like Miami, where the only mountains are made of trash and the water table gurgles just a few feet below the porous limestone beneath our feet, on the surface it may seem like we have little use for them.

In reality, our eroding piece of shoreline is home to many tenuous networks of underground passage, whether built into the sand by hermit crabs or the concrete by artists. Take, for example, Tunnel, a project room and artist residency located beneath a shopping center on a bright street in Miami’s Little Havana. On the ground level, there are no visible signs that indicate where this supposedly public gallery might be—instead, you know you’re in the right spot, which is to say almost directly above it, if you’re standing catty-corner from the 7-11 at SW 12th Ave and SW 3rd St. To reach the promised exhibition of contemporary art that lies below, visitors must first undertake an Orphic journey underground, past an ominous squad of chickens, squawking like a three-headed guard, and then down a twisting car ramp, before facing their final test in a large parking lot, dotted with the dusty vehicles of those who dared to venture this far before. There, in the dark cavern below, is a fishbowl-windowed room of bright white light. But rest assured; no final judgement awaits, at least not yet. Behind it, a wrought iron gate leads to an interlocking warren of shared studio spaces that tunnel into a series of pardoned-off rooms.

Perhaps it makes sense that so much of the work made in this car grotto feels somewhat purgatorial, architectural, or concerned with the artist’s place in relation to commerce and the machine. Resident David Correa’s sculptures feature combustion engines that rev like a highway on a Saturday night and spew choking exhaust at those lucky enough to witness his performances; Alicia Bilbao tears apart Miu Miu ballet flats and carefully recreates them as miniature versions for her wide-eyed, phone-clutching dolls. Luna Palazzolo-Daboul, who administers the space, fabricates sculptures from concrete and rusted rebar, and has a small house constructed from matchsticks in the corner of her studio; she acknowledged in an interview how the brutalist, concrete nature of these surroundings are a part of the appeal. Her work is evocative of the construction sites and skeletal forms of future apartments that fill many parts of Miami, but have mostly avoided this neighborhood.

Before this space came into her hands, it was used as a friend’s recording space, and two-and-a-half years later, the same music-themed murals they left behind still fill the enclosed car park outside the studio. This continuity is reflective of the collective’s ethos, which is to create space to produce and display work, without completely transforming the neighborhood that surrounds it. The shopping center above Tunnel is home to a small charter school, two salons, an unemployment office, and a pharmacy, as well as a small window exhibition space known as Touché Boutique, whose displays of slowly melting sugar sculptures by Victoria Ravelo or virus-themed performance art by Hush Fell are usually the only signs that something unusual may be occurring below the surface.

I first encountered Tunnel during Miami Art Week in December 2023, when it co hosted an exhibition with the Brooklyn-based Flower Shop Collective, inside a vacant storefront above ground. Titled an archive is a space for gathering and curated by Miami-born Palestinian American artist Nadia Tahoun, this exhibition faced out directly on to the street with well-lit windows, and featured multidisciplinary work explicitly concerned with addressing the ongoing genocide in Gaza. During a week of the year which is usually more about commerce than community, Tunnel made space for real dialogue and connection, with a full slate of public programs including a poetry reading, a musical performance honoring a defunct local punk venue, and bilingual curatorial tours. Discovering Tunnel at that moment meant discovering much more than a space for consuming art; it felt like finding the only place in town where people were able to freely talk to each other about how to work collectively as we barrel toward increasingly uncertain futures.

This feeling has only proved true over time: In 2024, Tunnel hosted Elias Rischmawi’s solo exhibition A Memory of Love and Loyalty, which included family heirlooms and archival photographs of the artist’s family, taken in Palestine, Chile, and Miami. In the artist’s own words, the show functioned as a rebuke to the idea that their homeland is “a land with no people.” Since its opening, Tunnel has provided curators like Tahoun and artists like Rischmawi a free space to engage in powerful forms of institutional critique in a city where censorship is increasingly becoming normalized.

As an entirely artist-run project space, not beholden to any Miami donors or funds from the Florida government, Tunnel’s exhibition room is a nimble enough entity to house work from various different disciplines, even hosting an anonymous artist last summer. Its small size makes it relatively easy for artists to cheaply create immersive settings that might be lost in a more open and above-ground setting.

This winter, Tunnel presented Mate Masie, an exhibition of drawings made by North Carolina-born artist Najja Moon, who had painted the small room the bright, digital blue, like the color of an unclicked link. The floor was covered with a plastic laminate to mimic the slick wooden floor of an indoor basketball court. In the corner, the artist propped a door, which had a small basket attached to it; a few toy balls were left on top, so to encourage a kind of casual engagement with the artwork as a kind of game.

A tight grid of 347 small abstract drawings the size and shape of basketball cards were installed on the gallery walls, as if Tunnel were displaying a particularly zealous fan’s collection. But there were no faces, hometowns, or statistics breaking down each player’s stats into clean numbers or averages. Moon’s work is about the real love of the game – a communion with the choreographies that underlie our everyday choices, and the rhythms of interaction these movements suggest about life lived communally. Simple, jagged lines or swirling loops and circles depict different pathways, that together read as a profound meditation on the maze-like nature of eking out an existence in whatever mess is passing for a society these days.

Here, twisting arrows and dotted dribbles mimicked a coach’s hand-drawn plan for a perfect game, or a dancer’s movement across a partner-less floor. The title of the show, Mate Masie comes from a Ghanaian Adinkra symbol meaning “what I hear, I keep,” referring to a kind of naturally embodied knowledge that Moon channels through her automatic drawing style. “It’s sort of like the phrase: when somebody shows you who they are, believe them. But not in a negative way, it’s more internalized,” Moon explained. “More like, you know who you are by looking back at the actions you’ve taken, and they define you.”

Moon’s exhibition and her personal path in life have been rooted in activating community, so it feels appropriate to see her work in this context, surrounded by supporting teammates. “Probably the best thing about having my first [solo] show here is that it is such an honor to have been invited by other artists,” Moon shared. “It’s so important to me to show up for other people, and to be asked by my community like that means a lot.” In the past, Moon’s projects have included a photobooth that dispenses poetry based on the querent’s age and a custom-designed basketball court in a local public park, produced with Project Backboard. In addition to traditional galleries, Moon often produces work for public places; one encounters it in unexpected spots in the city, places of play where the work is more likely to be collectively enjoyed.

For a solo commission on the plaza at the Museum of Contemporary Art in North Miami in 2022, Moon produced a larger version of these drawings as a kind of gigantic game of life, with curving arrows and text asking questions like, “Am I good enough?” and “Am I in love?” Printed on clear plexiglass, the Florida sun projected Moon’s text and drawing on to the concrete sidewalk in front of the museum like a chalk hopscotch game, encouraging passersby to follow the lines and jump to answers of “yes” or “no” in a game that recalled the physical play of childhood while encouraging reflection on the choices we make as adults, and how those choices construct our shared reality.

The fleeting movement of a conductor’s hands can be seen in the routes that Moon lines across the space of a page. Moon first connected this origin for her work when she took long exposure photographs of her own hands guiding a choir. “What was left behind were marks that look like the drawings that I make,” she shared. She grew up the child of a minister, and remembers running and dancing between the pews to distract the singers as her mother would try to lead them. Moon thinks of her work as an abstraction of her memory of this play. Her emphasis on the communal nature of the team may also relate back to hearing these singers’ voices, layering over one another to amplify a collective call.

More than any pervading feeling of hope or fear, the overwhelming sense one gets when looking at a turn in Moon’s line making is that the only constant in life is change—and our only role is to play an active part in shaping it.

Installation view of Mate Masie by Najja Moon at Tunnel Projects. Image courtesy of the artist.

Installation view of Mate Masie by Najja Moon at Tunnel Projects. Image courtesy of the artist.

Installation view of Mate Masie by Najja Moon at Tunnel Projects. Image courtesy of the artist.

Francess Archer Dunbar is a writer and poet. She teaches and archives student poetry with O, Miami’s Sunroom program in public schools, and previously worked with the Miami Book Fair and served on the screening committee for the 41st Miami Film Festival. Her writing about her hometown can be found in Burnaway Magazine, the Art Newspaper, and the Miami New Times.