On Viewing Rooms: Displaying Pictures Void of Contexts, Absent Deliberation

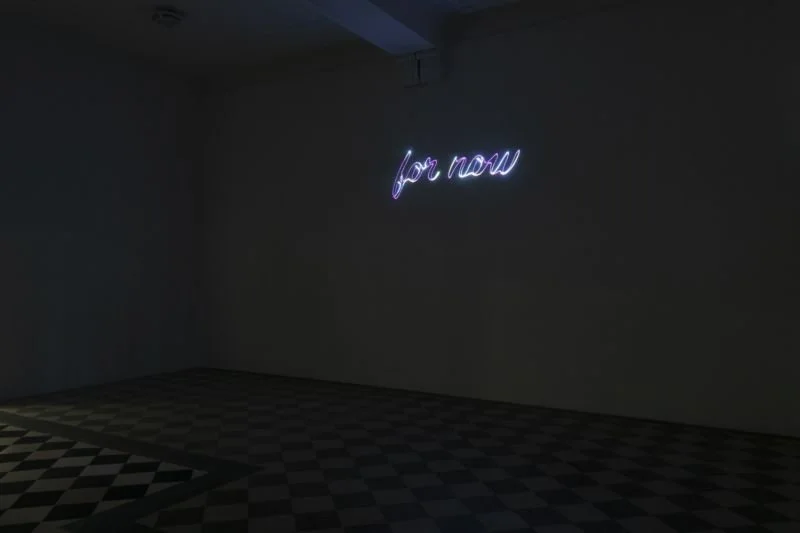

Nicole Miller, For Now, 2018, installation view, Kristina Kite Gallery, Los Angeles. Featured on Galleryplatform.LA.

By Sue Spaid | July 01, 2020

Art Critics on Emergency is a real-time collective diary by AICA-USA members about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on art critics, artists, arts institutions, art education, and the arts at large. AICA-USA members are invited to submit journalistic reflections and critical observations about this moment as it unfolds.

"Knowing full well that a transformation is underfoot, it’s increasingly

clear that what we consider art today and how we currently experience

it will no doubt change a lot by 2030, the year UNIPCC has identified

as the last chance to drastically reduce carbon emissions....I imagine

there will be many more museum exhibitions comprised of artworks from

the museum’s collections, local artists and local collectors....If museums

stop shipping particular artworks across the globe to be assembled en

masse, provenance may one day be irrelevant. As such, artworks’

contexts may vary less over centuries and their presentational histories

might reflect published rather than exhibited presentations, enabling art

writers to resume responsibilities lost to curators, during the era when

exhibitions held sway. Finally, I worry that firsthand experiences with

contemporary art will only occur in commercial venues, such as auction

houses, art fairs and galleries. No doubt, the next decade will inspire/force huge transformations in visual art."

When I penned these words for the preface to my forthcoming book, The Philosophy of Curatorial Practice: Between Work and World, I could never have imagined commercial venues being closed to the public, let alone for months on end. Throughout this book I claim that firsthand experiences prompt spectators’ thoughts about art, thus inspiring those ideas and memories that eventually inform art history. The twin features of curated exhibitions are public reception and the significance of relational objects, such that artworks are the kinds of things whose contents reflect their contexts. This book not only enumerates the many parallels between curating and art criticism, but it emphasizes the significance of public deliberation, typically spurred by exhibitions and articles.

I wrote these words because I imagine climate-change activists pressuring public institutions to slash their carbon footprints, leading international exhibitions of contemporary art to become obsolete. Problem is, even if writing about contemporary art releases far fewer greenhouse gases than exhibiting it, it’s extremely difficult to write about things sight unseen. Following the closure of Art in America’s offices Editor-in-chief William S. Smith sent his staff this morale-boosting message: “Art criticism is usually a secondary experience, a discussion of works in a museum or gallery. During a pandemic, the situation is different. Art criticism is a primary way for people to engage with art. That’s a responsibility we have to take seriously.” To my lights, his view dovetails with the sentiment expressed above. Art writing has never mattered more, as the following assessment of the “viewing room” fad concludes.

Mid-March, we all received a massive wave of emails apologizing for cancelled exhibitions with promises to keep in touch. How this would pan out was anyone’s guess. Treating art like click bait, galleries taunted us with rare art opportunities (you can’t really call them experiences). At first I was bowled over by the flurry of activity. Like a species whose habitat was rapidly disappearing, I found myself thrown into adaptation mode, seeking nourishment from whatever got tossed my way: artists’ pandemic responses, garden interviews, video premieres, book launches, live chats, and even downloadable art. I loved watching Cecilia Vicuña read her latest poem “We are our virus.” I was awestruck by a segment of “Let’s Paint TV,” during which John Kilduff made a drawing based on callers’ suggestions, while running on a treadmill and cooking pancakes. Given the huge effort to avail art’s abundance I felt genuinely obligated to participate. But as Los Angeles based sculptor Pat Nickell (also Director of Nan Rae Gallery) wrote me, “Good Grief! We are destroying first person experience!”

Soon after, museums got into the spirit with online yoga, DJ’s, video premieres, movie nights, recorded interviews, collection highlights, curator-led tours, and a haiku-soliciting sound artist. Even AICA members shared their lists of novel events. With so many offerings, scheduling soon became a daunting task, since everything seemed to happen at once. To top it off, the Met opted to stream its ordinarily exclusive gala on Vogue’s youtube channel. Eager to lure captive audiences, institutions definitely exposed art more broadly, but it’s difficult to assess how truly special their efforts were.

Those of us living in Europe are now getting hit with a second wave of emails telling us which exhibitions are extended and how to prepare for the artworld’s reopening, which will require masks and/or online reservations to guarantee entry. For me, COVID-19’s biggest exhibition-related tragedy was the MSK Gent’s inability to extend its once-in-a-lifetime exhibition Van Eyck: an Optical Illusion, which went dark halfway through its scheduled three month run. It coincided with a citywide festival, organized to celebrate the end of the eight-year long restoration of The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb on view nearby at Saint Bavo’s Cathedral. I imagine that every art critic could identify similar tragedies.

Detail from The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb before (left) and after restoration.

But lest we forget what just happened, a moment of reflection is due, especially since I fear that we are left with one lasting consequence: the “viewing room.” Branded a breakthrough, Art Basel Hong Kong 2020 (held March 20-25 with two days of VIP previews) attracted 250,000 visitors (nine times more than that of TEFAF and six times the Armory Show’s visitor count, both held two weeks earlier) and generated plenty of big-ticket sales, proving that online art fairs can reach buyers ordinarily out of reach. One surprising twist is that so far online art fairs list prices, granting a level of transparency atypical of most fairs.

Inspired by David Zwirner Gallery’s viewing room, which has been online since 2017, many galleries started launching their own, followed by two multi-gallery consortiums (GalleryPlatform.LA in Los Angeles and “Restons Unis” in Paris), and then Frieze Viewing Room and Not Cancelled (held globally, May 8-15). Viewing Rooms-Art Basel recently ended. At first I was totally impressed by the galleries’ ingenuity and genuine concern to keep it going, if not for their clients then for their artists, many of whom seemed to be creating artworks especially geared toward this moment. But now I find myself wondering what viewing rooms offer that galleries’ up-to-date websites don’t. At least with websites there are titles and dates if not bios and bibliographies. I can’t tell you how many emails I received inviting me to visit a gallery’s viewing room as anonymous artworks flashed by, not to mention the annoying required registration. Perhaps this is a natural outcrop of Instagram, Pinterest or Twitter, where nameless pictures reign supreme. But as gallerist Daniel Templon recently told Le Monde, “online viewing rooms are no substitute for the physical confrontation with artworks.”

Trying to grasp viewing rooms’ popularity, I spent the better half of an evening visiting the Frieze Viewing Room. I found the criteria used to narrow searches a bit surprising: continent, gender (five options), art fair hierarchies (Frieze sub-sections) and price. The idea of using nonart categories to select artworks seems odd. Are there really collectors searching for art costing less than €100,00, made by non-binary artists inhabiting Oceania? Whatever happened to aesthetic and historical categories like abstract, figurative, conceptual, sculpture, painting, video, or decades? Of course, search engines can quickly identify the right Lisa Yuskavage on offer, but search engines can’t be unique to online art fair viewing rooms. There must be software capable of combing gallery websites to pool searchable inventories, though I imagine securing prices proves difficult.

Although I rarely visit art fairs, I’m fascinated by technology’s efforts to refashion the artworld in its own image, which includes the appointment of Jarvis, an artificial intelligence program, as curator of the 2022 Bucharest Biennial. Too bad for artists who lack searchable names and frames, let alone websites. One major disadvantage of viewing rooms is that if one doesn’t already know the artist’s oeuvre, one is out of luck, since viewing rooms only have space for about 300-word introductions, which is ok for a solo show, but disastrous for artworks by multiple artists.

Getting back to those non-art categories that enable people to narrow their searches, it’s clear that this whole thing is rigged for “big data,” so market researchers can sell what they’ve scooped up from online fair visitors. This was already a worry with live art fairs, as Margaret Carrigan reported last year in the Art Newspaper. She noted how UBS Art Basel’s annual Art Market Report (an annual subscription costs $1200) lures investors with data’s revolutionary power, enabling “intel” to replace connoisseurship. If online viewing rooms are anything like google searches, viewing room visits are likely to haunt our email inboxes.

So long as we continue to battle waves of COVID-19, I’m afraid viewing rooms are here to stay. I thus end with a few notable alternatives. Rather than offering virtual exhibitions, as Franklin Einspruch’s insightful article describes, the following inspire thoughts that engender public deliberation, much like art criticism. My favorite by miles is the virtual exhibition Patterns II, curated by Chicago painter Michelle Grabner for Anne Mosseri-Marlio Galerie in Basel. Its installation views provide vital information lost to artworks presented as singletons. With transcontinental flights up in the air, Mosseri-Marlio could not guarantee return shipping, so she asked her photographer Serge Hasenböhler to insert images (adjusted for perspective) into extant installation shots, giving online viewers the sense of what visiting this show would be like. Similarly, the bi-coastal fortgansevoort.com invited curators Terry R. Myers and Alison Gingeras to organize online exhibitions presented as singletons, though accompanied by context-providing texts. London galleries have launched Vortic, an extended reality (XR) platform that works with an Oculus VR headset to simulate immersive viewing, even allowing one to “try out” artworks in one’s own living space.

Installation view, Patterns II at Anne Mosseri-Marlio Galerie, Basel.

What we rather need is “viewing zoom,” where we can conduct public conversations about what is being shown as opposed to posting anonymous comments as online platforms ordinarily allow. A platform like “viewing zoom” would also improve upon ordinary art fairs, since rather than depending on the gallery’s sales pitch, one could hear multiple perspectives and reflections, thus persuading many more people of the displayed artworks’ merits. Even if the objects of said conversations are mere images of absent things, I imagine them thoughtfully displayed, more like exhibitions than available stock, visible one at a time.

The author of five books on art and ecology, Belgium-based curator and philosopher Sue Spaid contributes reviews to the Flemish art magazine HArt and regularly publishes papers on aesthetics and environmental philosophy in journals.