Thoughts on Doom

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (Burning House), spray paint on paper, 1982.

By Eleanor Heartney | April 5, 2020

Art Critics on Emergency is a real-time collective diary by AICA-USA members about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on art critics, artists, arts institutions, art education, and the arts at large. AICA-USA members are invited to submit journalistic reflections and critical observations about this moment as it unfolds.

From the coronavirus to the Australian fires (now already receding in memory) along with assorted earthquakes, hurricanes, floods and droughts, current events are placing Doomsday in the forefront of our minds. While I don’t claim to be a seer, last year I published a book titled Doomsday Dreams: The Apocalyptic Imagination in Contemporary Art. I was interested in how religious ideas derived from the Book of Revelation and other apocalyptic narratives frame our responses to calamity in ways that may prevent us from finding actual solutions to real problems.

This inquiry has acquired a new urgency with the current pandemic. Trump and his supporters are attempting to fashion this crisis as a threat foisted on us by external enemies. This invasive force, they argue, requires a war-like response. By girding for battle against an alien entity (first the “Chinese virus”, then foreigners potentially carrying the virus who should be blocked at the border, and now New Yorkers—those un-American creatures who failed to vote for Trump and who now must be prevented from infecting others outside the city limits) the administration can deflect attention from its own shortfalls in planning and the failings of our for-profit healthcare model. Nor is Trump alone is using the military metaphor. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has likened the need for ventilators to the wartime need for missiles. After much equivocating the Administration is flexing war powers to force industry to produce the necessary equipment.

But is war the right metaphor? Or is it just the fall back position hard wired into our brains when we are faced with life threatening dangers? Haunting our response to this pandemic is an ancient text. In the Book of Revelation, the first century visionary John of Patmos provides the perfect apocalyptic trope for the coronovirus. He prophesizes that Armageddon will be preceded by the appearance of four horsemen unleashed upon the world as retribution for the sins of mankind. The first three horsemen represent Conquest, War and Famine. But the most fearsome of the horsemen is the last. According to Rev 6:8, “I looked, and there before me was a pale horse! Its rider was named Death, and Hades was following close behind him. They were given power over a fourth of the earth to kill by sword, famine and plague, and by the wild beasts of the earth.”

Albrecht Dürer, The Four Horsemen, from The Apocalypse, woodcut, 1498. From metmuseum.org.

The spectre of the Pale Horse runs through western history. Durer’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1498) is an iconic illustration of this passage. In it, under the guidance of the angel of death, his four horsemen charge forward, pummeling unhappy people under foot. While the other three horsemen are robust warriors, Death is a spectral figure, almost skeletal as he leaps over the demons swallowing hapless humans. Other notable visions of the Pale Rider were created by artists like John Hamilton Mortimer, Benjamin West and J. M. W. Turner. The latter’s Death on a Pale Horse (1825) is particularly haunting. Turner erases all actors but the shadowy horse and skeletal rider who lies draped over his steed like a casualty himself. The whole painting is enveloped in a fiery mist that suggests the obliteration not just of the damned but of all reality.

In the fourteenth century the Black Death appeared to herald the literal arrival of the Pale Rider. Over the course of four years up to a third of the population of Europe died, with corpses piling up while the priests enjoined to administer Last Rites themselves fell dead. Searching for an explanation for this suffering, people fell back on a familiar villain. In The Distant Mirror, her study of the calamitous 14th century, Barbara Tuchman notes, “While Divine punishment was accepted as the plague’s source, people in their misery still looked for a human agent upon whom to vent the hostility that could not be vented on God. The Jew, as the eternal stranger, was the most obvious target.” She recounts how Jews were rounded up en masse, tortured and burned alive.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Death on a Pale Horse, oil on canvas, 1825–30. From tate.org.uk.

Then, as now, apocalyptic thinking interfered with people’s ability to deal with crises by encouraging scapegoating, fatalism and division. It's a pattern that is repeated again and again in the course of pandemics. Jews, rather than infected rats, were blamed for the Black Death. Homosexuals were shunned as the cause of the AIDS crisis. Immigrants were considered the culprits in the dissemination of swine flu. In all such cases, contagion was construed as the manifestation of an evil that must be purged from the earth. The assignment of blame became the necessary prelude to the cure and purification of survivors.

Today, conspiracy theories abound as to the origin of the coronavirus. The epidemic has been blamed on “unnatural practices” like the human ingestion of bats. It has been described as a bio-weapon developed by—you choose—the US, Israel, North Korea or China. It is, according to various Fox News commentators, a hoax dreamed up by Democrats and the liberal media to re-impeach the President. However, approaching the pandemic as an enemy combatant diminishes our ability to deal with it. The slow response in the US was tied to the conviction that it was an external threat. Hence the surprise when it began to appear in people with no ties to foreigners or travel abroad.

One sees a similarly unhelpful pattern of apocalyptic thinking in our approach to other crises. Thinking about climate change gets bogged down in what Robert Smithson described as “ecological despair,” a belief in the inevitability of entropic decline and the losing battle of humanity against nature. Such thinking makes it difficult to envision practical solutions. And a lot of right wing nationalism is fueled by the conviction that immigrants and refugees are social contaminants who must be apocalyptically cleansed—an attitude that harks back to the Futurist poet Marinetti’s formulation that “War [is] the world’s only hygiene.”

It’s too early to expect any meaningful art about the coronavirus. But we might look back to David Wojnarowicz’ responses to the AIDS crisis for a way of thinking about our new pandemic. Wojnarowicz certainly saw the horrors unleashed by AIDS and was justifiably angry about the negligent institutional response to the epidemic. But even in his rage, he expressed a sweetness and an embrace of nature, beauty and love that are at odds with the apocalyptic mentality. In Wojnarowicz’s writings, it is striking how harsh descriptions of the struggle for survival on the street suddenly melt into moments of lyrical beauty experienced in the midst of an anonymous sexual encounter. Similarly, in his paintings and sculptures flashes of beauty break through images of the bleak devastation wrought by human action. Among his last works are paintings of exotic flowers overlaid with images and text that provide an interweaving of beauty and horror. As we hunker down at home and accept enforced separation from those we love, it is important to acknowledge the joys of life and the beauty of Spring breaking out all around us.

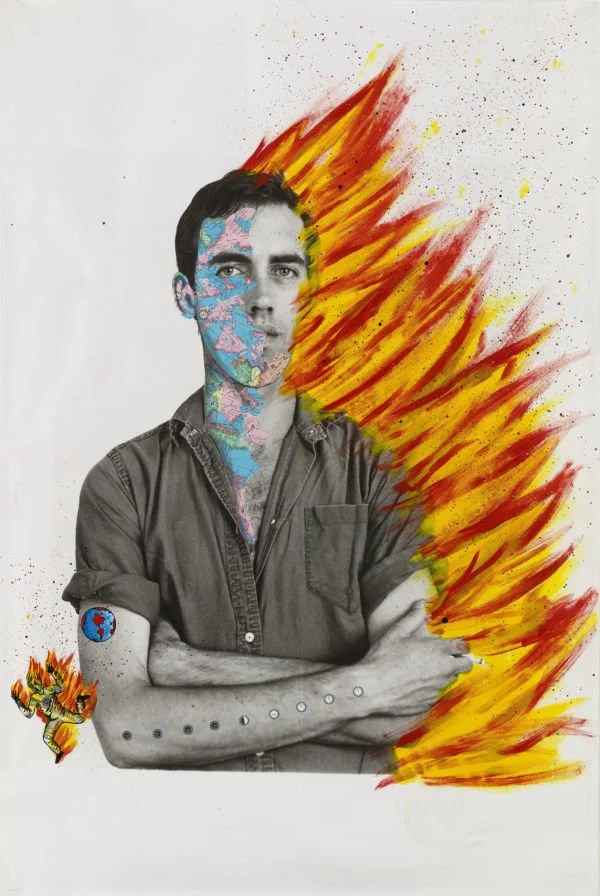

David Wojnarowicz with Tom Warren, Self-Portrait of David Wojnarowicz, acrylic and collaged paper on gelatin silver print, 1983–84. From whitney.org.

The world will be a very different place when we emerge from our social distancing. The economy, our political process, and our cultural and social institutions will all have taken a hit. And of course we still have no idea how many people will disappear from our lives. But the crisis offers an opportunity to reconsider our values and what is important to us as individuals and as a society. In a recent Artforum essay, Andrew Russeth took issue with the military metaphor, arguing that not war, but appeals to our common humanity will pull us out of this crisis. He opined, “This awful catastrophe will be overcome only by repeated, prolonged efforts—feeding people, testing them, treating them, cleaning public spaces, washing hands. The heroes are in maintenance. National Guard troops scrubbed children’s blocks in a school in New Rochelle when the virus hit there. All over the country, sanitation workers are picking up garbage and recycling, and workers at public schools are serving meals for children.”

Barbara Tuchman points out that individuals emerged from the Black Death no wiser or less sinful. But she also suggests that the skepticism it bred towards theocracy and an apparently merciless God were the first steps in the evolution of humanism. If we are lucky, this crisis will constructively reshape our priorities as well.

Eleanor Heartney is a New York based art writer and cultural critic who has been writing about art since 1981.