Floral Facades

Still, Belinda Kazeem-Kaminski, Unearthing. In Conversation (2017), 13 min, digital video

By Kayla Anderson | October 09, 2021

The Art Writing Workshop is a partnership between The Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant and AICA-USA. This program pairs ten emerging art writers with eminent voices in the field, facilitating deep critical engagement with art in regions across the US. 2020 Art Writing Workshop participants were invited to contribute a piece of writing that emerged from their work in the program for publication with AICA-USA's online magazine. What follows is one such contribution.

My grandmother could never keep flowers in her front yard. They would always disappear mysteriously overnight, ferried away in their pots, even sometimes uprooted from the ground. As a result, the inside of her house was full of flowers: printed on fabric and sculpted from thin metal. To complete the illusion, they were flocked by hanging ornaments in the shape of hummingbirds and butterflies.

She needed flowers that could flourish without sunlight because her curtains were always closed. I remember peeling them back one day and finding a bullet hole, which she told me was evidence of a previous tenants suicide. In retrospect I’m not sure why no one repaired the trace, but at the time it seemed fitting, in concert with a red handprint that would appear sometimes at night, too high up on the wall for any human to reach. She claimed that the house was haunted by several ghosts, cramped in tight quarters. She accepted their cohabitation in a matter-of-fact way. My mother had once awoken in the middle of the night to see a soldier rocking back and forth in a chair below the handprint. I never knew what war the soldier came from: was he a civil war apparition, here to remind us of Texas’s confederate past? Or was he simply one of the men my grandmother married in between those I knew as my grandad and grandpa: men who returned from Vietnam shell shocked, pacing the house at night with a gun in hand, ready to mistake a bleary-eyed stepchild for an enemy. After seeing him, my mother avoided sleeping over, leaving my sister and I to face our grandmother’s ghosts on our own.

But the flowers and their faithful pollinators knew nothing of the haunting. They were there to produce a fecundity I doubt she ever experienced. They stayed suspended in flight, in time, their vibrant colors becoming muted over the years from layers of tobacco smoke.

Personal photograph from the author

There’s a family photograph I’ve been looking at more these days, one that speaks of a different illusion. It’s a photograph of two young girls, maybe five or six years old, standing against a floral patterned couch atop a rag-rug in a small living room. The same tobacco has stained the walls the color of sand, made the mirror behind them opaque, offering no reflection.

The girls are wearing traditional Mexican dresses, the kind sold for Cinco de Mayo or Dieciséis de Septiembre. The girl on the left has a small nose and a soft oval face. She is tan, with brown hair that curves at her shoulders. She wears a flouncy folklorico dress with sections of red, white, and green. In her left hand she holds a pair of red maracas, looking down at her empty right hand with confusion: clutching the air. On her feet are bright white crew socks and metallic silver moccasins with a picture of Disney's Pocahontas on the toe.

The girl on the right wears matching silver sneakers with a cameo of Sleeping Beauty. She does not particularly like Sleeping Beauty, rather, her parents picked them out to match her complexion. She has a big nose and a long rectangular face. Pale, the flash bounces off of her, turning her hair white and her eyes red. She wears a white Puebla style dress with colorfully embroidered flowers. With her right hand, she cups the side of a small pink guitar. With her left, she gestures towards the strings like a robot in an animatronic band: her arm a rigid 90 degree angle, her hand flat, fingers glued together in the shape of an arrow.

Personal photograph from the author

She stares directly into the camera, her mouth a tight horizontal line. Her expression is confrontational, almost menacing. It's not hard to imagine her as a ghost that appeared in the photograph, revealed by the flash. The photographic act itself seems to be the focus of her antagonism. She holds the camera's gaze, tauntingly, as if to challenge the very constructedness of it all.

I first encountered Joiri Minaya’s Containers series on instagram. A friend found her in the National Portrait Gallery and posted her to the image-scape. There was something about the photographs that stuck to me, how they haunted the endless stream of house plant pics and satisfied selfies. I thought of her as a kind of trickster-heroine whose mission was to make fissures in the facades of exoticism, tropicality, identity, otherness.

Joiri Minaya, Container #4, 2020, Archival pigment print, 40 x 60 in

Minaya is an artist who works across photography, textiles, performance, video, and installation. Born in 1990 in New York City, she grew up in the Dominican Republic and returned to the US to complete her studies at Parsons in 2013. In an alternate life of mine (had I not freaked out about NYC rent prices) we would have been classmates.

Containers is an ongoing series of performative photographs, each featuring the artist posed in a seemingly natural environment while outfitted in a spandex bodysuit. The suits Minaya makes depict mostly foliage, sometimes ocean waves, rendered in repeat patterns that one might call "all over" prints, featuring equal proportions of figure (foliage) and ground (solid color). The patterns resemble a digital process called "content aware fill," wherein an algorithm analyzes the surrounding data in an image and fills in the selected area by generating a pattern based on perceived texture and color. The result of content aware fill is usually something visually congruous, but structurally or logistically implausible. Each suit corresponds to the environment in which Minaya poses, mimicking plant varieties, colors and textures. The abstracted patterns represent a kind of tropical imaginary: speculating on abundance while speaking in flatness.

There is no indication of where the individual photographs are taken, no visual markers as to their social or geographical context. One cannot even identify the plant species to determine the location, because Minaya reminds us that these are constructed environments. Does this tree live in its native habitat, or has it been transferred to an arboretum somewhere across the globe? Thanks to the global trafficking of tropical plants, one can't hazard a guess.

Joiri Minaya, Container #5, 2020, Archival pigment print, 40 x 60 in

In the first photograph of the series, made in 2015, Minaya is completely bound. She is lying on the concrete floor of a botanical garden, flanked on either side by lush but identical plants. She seems to have been taken hostage, muted and immobilized. Perhaps her captors stand behind the camera, hoping she'll simply blend in with the surrounding flora.

Joiri Minaya, Container #1, 2015, Archival pigment print, 40 x 60 in

Joiri Minaya, Container #2, 2016, Archival pigment print, 40 x 60 in

In the next image, from 2016, she stands facing the camera, but you can't make out her eyes. She emerges from the undergrowth of a dappled forest like an apparition. Her feet and arms are still bound, but her pose is statuesque rather than fetal. Her posture marks a shift in power: she might still be a hostage, but an assertive one. A goddess whose power cannot be curtailed.

Joiri Minaya, Container #3, 2017, Archival pigment print, 40 x 60 in

In the third image, made in 2017, you can make out the eyeholes of her suit just clearly enough to know that she is looking at you. This time her feet are free, anchored to the ground in a pyramid pose. She swivels her torso and lifts her still-bound arms above her head, leveraging her constraints to strike a familiar pose: reminiscent of a model in a swimsuit magazine. She stands ankle deep in the waves of a pristine beach, bisected by the horizon.

In an earlier collage series Woman-Landscape (On Opacity) Minaya cut women’s bodies out of photographs, filling their silhouettes with tropical patterns.

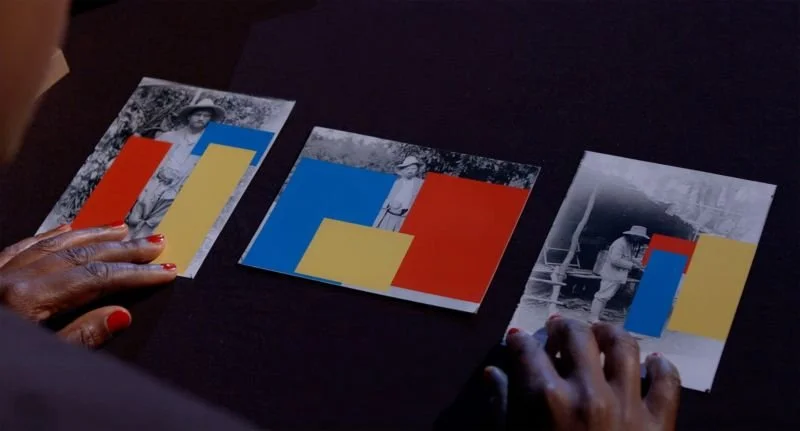

The gesture reminds me of the film Unearthing. In Conversation (2017) by Belinda Kazeem-Kaminski, wherein the artist reflects on her attempt to protect the subjects of colonial photographs taken by an ethnographer in the former Belgian Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) through various collage processes.[1] In one attempt, she cuts their bodies from the frame to leave black silhouettes. In another she covers them with rectangles in the colors of the DRC flag. As she handles the collages, Kazeem-Kaminski contemplates the difficulty of her task: to free these people from the photographs taken against their will; to rescue them from a history and present that still seeks to other them. While driven by care, she acknowledges that there is something violent in the cutting out, covering, and disappearing of these bodies. Why is it that the ethnographer gets to stand intact?

Still, Belinda Kazeem-Kaminski, Unearthing. In Conversation (2017), 13 min, digital video

In Containers, Minaya enacts the cut within the physical space of the image, an absence that is actually a presence. She writes "I've learned that there is a Gaze thrust upon me which others me. I turn it upon itself, mainly by seeming to fulfill its expectations, but instead sabotaging them, thus regaining power and agency."

Through Containers, Minaya preempts the stereotypes thrust upon her as a US born Dominican-United Statesian woman. She starts by playing into the colonial image through the settings and poses she assumes within the photographs. Through the visual incongruity, viewers are forced to confront what it is they expected to see, and how those expectations have themselves been constructed by a colonial agenda.

Minaya's work interrogates two interlinked conceptual tools of colonization that remain active in the neo-colonial West. First, the separation of "nature" from "culture" as a method for objectifying those that refuse to accord with Western models of development, constructing an ideological excuse for conquest, genocide, slavery, and the exploitation, extraction, and destruction of natural-cultural communities. Second, the construction of the "Tropics" as a more-than-geographical concept (as a foil to England's grey gloom) and with it, the stereotyping of people, especially women, as hyper-sexualized, exotic creatures ripe for the colonist's picking.

Minaya takes on the botanical garden as a legacy institution of colonization, alongside the commercial plant trade. Botanical gardens were established as a method for displaying the exploits of colonial expeditions for the enjoyment of colonial royalty and later, the public. Every house plant purchased in the United States whose species hails from Africa, Asia, South and Central America is a product of this ongoing legacy. It reminds me of the pro-immigration rallying cry penned by Sri Lankan-British novelist Ambalavaner Sivanandan, "We are here because you were there."[2] In Minaya's work, this truism is expanded beyond the human.

I first came across this phrase in an exhibition by Hương Ngô, printed in invisible agar-agar ink in English, French, and Vietnamese. The banners accompanied the installation In Passing I and the corresponding video Having Been Lost in Plain View, in which the artist uses a similar camouflaging technique to tell the story of Vietnamese revolutionary activist Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai, who was executed in 1941 by the French for conspiring against the colonial government. In the installation In Passing I, a silk habotai hangs in front of a backdrop depicting a mural from the Museum of the History of Immigration in Paris, printed so that it blends in with the background.

Hương Ngô, In Passing I, Archival pigment print on silk habotai, custom armature, 73 x 42 in, 2017

Hương Ngô, Having Been Lost in Plain View, Single channel digital video, Color, sound, 6:48, 2017

In the video Having Been Lost in Plain View, performers don the habotai from In Passing and stand in front of the backdrop, holding the camera's gaze. Here, the use of camouflage brings to mind Minh Khai's strategic concealment, blending into the colonial regime in order to work against it. Passing is a euphemism both for being perceived as a member of a different racial group (often appearing white in order to escape racial discrimination and segregation) and for dying. For Minh Khai, being recognized as an anti-colonial revolutionary resulted in her death.

Joiri Minaya, Container #7, 2020, Archival pigment print, 40 x 60 in

In Minaya's work, the title Containers brings to mind the literal ways in which the suits contain and constrain the artist's body, mirroring how botanical gardens confine their plant subjects. It also points to the facade-like nature of the concept of tropicality itself: created by the West as a container in which to hide the limits of its own knowledge, its fears of all that appeared contrary to its own self-image.

Camouflage is an evolutionary defense tactic used by humans and non-human organisms alike. To illustrate this, the Wikipedia article for camouflage features two images side-by-side, both taken in places ensnared in lingering colonial relationships with the United States: 1) a peacock flounder living off the coast of Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, and 2) an American soldier applying face paint for a test operation on Vieques island, Puerto Rico. Camouflage is a natural-cultural phenomenon. It is a strategy used by both colonizer and colonized.

In her analysis of slave song, Saidiya Hartman argues that when "considered in relation to...the degrading hypervisibility of the enslaved...concealment should be considered a form of resistance."[3] Hartman writes this in concert with Eduardo Glissant, who advises that "the attempt to approach a reality so hidden from view cannot be organized in terms of a series of clarifications.” Rather than be seen, the decision to remain illegible or opaque to the colonial gaze is a practice of agency and control.[4]

One morning from the shower, I overheard a short interview on NPR that, like Minaya's photographs, also stuck to me. In the segment, journalist Ari Shapiro asked his interviewee, entrepreneur and community advocate Monika Matthews, if she felt "seen."

Matthews, owner of the body care shop QueenCare, had just expressed how her stress levels had skyrocketed while adapting to Covid-19 business safety precautions with no support from the government. "Do you feel seen?" Shapiro asked her. His vocal tone rang with a kind of inspo-glow that seemed dissonant with Matthew's words thus far. "Seen…?" she asked, with a bit of audible confusion. Perhaps diplomatically, she added "can you clarify that question?"

Pointing to the death of George Floyd and ongoing protests by the Black Lives Matter movement, he reiterated the question. "Oh," she replied, taking a moment to let it sink in.[5]

She went on to explain that yes, while there had been more spotlighting of Black-owned businesses in response to racial injustice, unfortunately when it came to financial support, she did not feel seen. But more importantly, it was clear from her reaction that being seen was not her primary concern. Being seen is not the same as being supported, as being safe. Being seen does not guarantee that you are given what you need to survive, much less thrive. Visibility is not synonymous with equity.

The contextual ignorance of the question revealed the inadequacy of the contemporary platitude I feel seen. It gleefully skips over the ways in which racialized and marginalized people are made simultaneously invisible and hyper-visible. On the contrary, it assumes that any form of visibility is positive.

Certainly, in this turn of phrase "seen" is meant as understood on a deeper-than-surface level, not simply registered by the eyes. However, its increasingly frequent usage places a great deal of importance on visibility as the primary answer to oppression and injustice. As Matthews' reply exemplifies, visibility is never the end goal of anti-racist, decolonial, nor feminist, politics.

Containers is not about being seen. In fact, you could almost say that Containers is about not being seen. But it's also not as simple as that. In Containers, Minaya is seen in the act of disappearing, or rather, seen to be hiding in plain sight. What is seen about the figures in Containers is that they cannot be made legible by a mere surface reading, nor captured and co-opted as an ethnographic image. What is made hyper-visible in the series is the facade of tropicality that Minaya and her performers are contained within. It is the hypervisibility of the colonial gaze that has obscured them from view.

In the essay "Outside In Inside Out," Trinh T. Minh-ha states that for the colonizer, "the ideal insider is the psychological conflict-detecting and problem-solving subject who faithfully represents the Other for the Master."[6] Minaya's figures refuse to be ideal insiders by failing to represent anything other than the flatness and incongruity of the facade projected upon them. In a performance version of Containers, the figure in green asks, "was invisibility self chosen and kept as an evolutionary trait, or is it a colonial imposition?" The truth, and tragedy, is that we will never know.

In its migration north from San Antonio, Texas to Chicago, Illinois, the photograph of my sister and I has become a kind of oddity. I've learned two things about this photograph through its contextual shift. The first is that I should never show it to anyone unless I want to face ridicule for cultural appropriation. The second is that in it, my sister's ability to blend in back home, to not be seen as the strange pale child, in the Midwest might be called passing.

This thought enters my mind retrospectively, after a friend asks if we can pretend to be Mexican in order to blend in to our soon-to-be gentrifying neighborhood. It takes root after becoming part of academic environments that systematically segregate people into categories of white and not-white based on appearance, without any additional regard or interest in things like heritage, language, and nationality. While offered up as well-meaning attempts towards visibility, they tend to lack any complexity.

While Chicago is not an exceptionally white city, it has always felt that way to me due to its neighborhood segregation. When I first arrived ten years ago, I was shocked by how little I heard Spanish spoken at my school, only to ride the train 30 minutes out and find myself in a neighborhood that sounded like home. It was here that I understood that all the stereotypes I was fed of the Northern United States as more cultured than where I grew up actually meant more white.

To grow up in Texas is often to grow up hating it: to be surrounded by macho slogans, quick-firing guns, and haunted Spanish colonial missions. Meanwhile up North, you hear, there are fewer churches and more culture. There are ivy league colleges and intellectual traditions. There are people speaking all kinds of languages, from all kinds of places—as if the same is not true of your own city. It took me leaving to realize that the place I grew up in is full of culture, it just wasn't exceptionally white.

In 2013, Sebastien de la Cruz, an 11 year old musical prodigy from San Antonio, was lambasted on the internet for singing the national anthem while dressed in a charro suit.[7] The Spurs were playing the Miami Heat, and de la Cruz had been chosen to open the game after winning a singing competition. The internet concluded that his attire and appearance were un-American. In response to the slew of racist comments, the team responded that clearly these people commenting were not from San Antonio, and had no understanding of the city. How ignorant were they to suggest that his attire, something based in local history and tradition, was not appropriate for the occasion? Didn't they know anything about our culture?

In San Antonio, whiteness is present, but it's not the cultural default. Growing up, I assumed the rest of the United States was like this. I couldn't fathom a North where white kids went to school with mostly other white kids, or where Spanish was spoken only in classrooms. A North where people could believe the immigration narrative of a white place being infiltrated by non-white others, when in fact, colonization and immigration had enabled the reverse: a population that became more white, less brown and indigenous over time.

But even San Antonio is not free of racism or white supremacy. Once at Beto's, a Cuban restaurant that rebranded itself as Mexican after fears of communism, I found a flier for a Latinx branch of the Greek neo-nazi party Golden Dawn. Whiteness is not absent, but rather it is shifting, complicated.

Stock image of the San Antonio River Walk

Ten years ago, when I would try to explain San Antonio to my classmates in Chicago, I would show them pictures of the river walk, which always left them with a false sense of luxury. It didn't speak of the gun violence, the overcrowded school system, or the beguiling lack of affordable fresh produce. Instead, I showed them a facade of festivity, celebrating a lost battle whose real (and unacknowledged) impetus was to uphold slavery. A city whose flowers are made primarily of brightly colored tissue paper.

My sister would later remember the events of the photograph as "the day we went to Mexico," at which my mother would burst out laughing—we had actually only gone downtown. El Mercado, San Antonio's historic market square, is a willing confusion: made for tourists but frequented by locals, its complex of tiny shops offering Tex-Mex takeaways made in Guatemala. This is on par with the rest of the city's downtown: a historic Mexican restaurant founded by German immigrants, flocked by shops lining a man-made river. A place where authenticity is hardly an option.

Photograph of El Mercado from San Antonio's official Parks and Recreation website

But in San Antonio whiteness is visible. One is aware of being white, just as one is aware of lacking fluency in Spanish. And because San Antonio is a city that celebrates facades, you could say that whiteness is visible as a facade—visible as a construct, a contract with Western notions of power. It was never Pure Michigan.

It is only in the context of perceived purity that the photograph of my sister and I becomes visually incongruous. It does not fit into a discourse that seeks to draw clean delineations between insider and outsider, between authentic identity and mere appropriation.

In the photograph of my sister and I, what I see is this: that we are indebted to cultures that are not ours. That what is ours is questionable, since our parents have given up their connections to both Jewish (by choice) and Indigenous (by force) cultural communities. What is ours will always be borrowed. Authenticity will always be troubled.

In her final essay for the journal Tropiques, "Le Grand Camouflage," Suzanne Césaire writes that while it is one thing to recognize the contemporary and historical disjunctions that French colonization has wrought upon Martinican identity, society, and culture, it is another to acknowledge the ways in which French culture, nationhood, and identity have also been transformed in the colonial process. She asserts instead that the histories and subjectivities of both nations will be forever altered by the colonial relationship, forever entangled with one another.

The act of colonial violence also disfigures the perpetrators, who must repeatedly cope with the consequence of their actions: developing new compensations and self-explanations. Of the white French population Césaire wrote, "they dare not recognize themselves in this ambiguous being, the West Indian man."[8]

In Containers, Minaya does not seek to be recognized by a white colonial or neo-colonial audience. Rather, Containers suggests that white viewers look at themselves a little more clearly, with what Césaire called lucidite totale, to recognize their role in creating the container to which they confine her; their ongoing complicity in her withdrawal.

It is this kind of seeing that I believe Minaya's work does call for: a recognition of the myriad colonial legacies that dictate daily life in places like the United States. These legacies, like the botanical garden, appear benign thanks to the cultural production of ignorance. The colonizer is made to believe that they survived the process unscathed, that their own identity is neither fractured nor irrevocably troubled.

In order to end public lynching in the United States, Black activists created campaigns to reveal to white people the ways in which their actions rendered them morally depraved.[9] Perhaps Minaya's work suggests that a similar education is still forthcoming.

1. Unearthing. In Conversation, by Belinda Kazeem-Kaminski (2017; Vienna, AT; Sixpack Films).

2. Virou Srilangarajah, “We Are Here Because You Were With Us: Remembering A. Sivanandan (1923–2018),” Verso Blog, February 7, 2018.

3. Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 36.

4. Alexander G. Weheliye, Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014).

5. Ari Shapiro, “All Things Considered,” Interview with Monika Matthews, KQED 88.5 FM, March 4, 2021.

6. Trinh T. Minh-Ha, When the Moon Waxes Red: Representation, Gender and Cultural Politics (New York: Routledge, 1991), 68.

7. Colby Itkowitz, “He endured racist attacks after singing at NBA game. Now he’s the opener for the Democratic debate,” The Washington Post, March 9, 2016.

8. Aimé Césaire and René Ménil, Tropiques (Paris: Jean-Michel Place, 1978).

9. José Medina, “Racial Violence, Emotional Friction, and Epistemic Activism,” Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 24:4 (2019), 22 - 37.